A Road Map to Increasing Faculty Diversity

A nationwide collaboration of biomedical engineering faculty provides a roadmap for overhauling faculty-hiring processes to eliminate barriers of entry to historically excluded groups.

In recent years, universities across the United States have made increasing diversity an explicit goal, and increasing faculty diversity an important aim within that larger objective. Realizing diversity goals has proven difficult, however. To try to address the challenge, faculty members from sixteen top university biomedical engineering programs across the country — including Beth Pruitt, professor and chair of Biological Engineering at UC Santa Barbara — spent two years collaborating to develop an explicit six-step roadmap for institutions, programs, and departments that are seeking to achieve the elusive goal of increasing faculty diversity and representation.

"We hope that this manuscript will help faculty identify and take actionable steps to mitigate misperceptions, biases, and barriers to equitable and inclusive search and hiring practices,” Pruitt said.

The authors describe the plan in a paper titled “Diversify Your Faculty: A Roadmap for Equitable Hiring Strategies,” published in the August 14 issue of the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering. It includes steps that faculty and administrators should take “to overhaul their hiring processes if they are serious about diversifying the academy.”

“You can't just say, ‘It’s not our fault, we don't get the applicants.’ That’s passing the buck,” said Elizabeth Cosgriff-Hernandez, a professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Department of Biomedical Engineering at The University of Texas, Austin. “If you want to change the diversity of your hiring program, you have to change how you’re getting applicants and how you evaluate them.”

The researchers emphasize the importance of developing consistent rubrics with fleshed-out criteria to evaluate candidates. They cite studies showing that a lack of such criteria leads to less diverse hiring and what is called sliding bias. For example, without strict criteria, Cosgriff-Hernandez says, “If a hiring manager likes someone, whatever qualities that person has can become the priority for the position. People tend to be biased toward people they like and who are like them.”

Pruitt explained that the paper emerged from a discussion started in BME UNITE, a network of hundreds of biomedical engineering faculty who are interested in educating themselves, improving representation, and combating racism in STEM. The working group and eventual co-authors of the paper emerged under the leadership of Cosgriff-Hernandez. It included researchers from top BioE programs who self-identified as being interested in and experienced with the literature on the topic, and who share a desire to identify and recommend best hiring practices to increase diversity in the faculty ranks at their respective institutions.

The paper begins with an unequivocal assertion: “Hiring practices in academia have critically limited the entry of individuals from historically excluded groups (e.g., people who identify as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, American Indian/Alaskan Native, LGBTQ+, people with disabilities) into our biomedical engineering faculty….Excluding such individuals has hindered our profession’s research impact and its ability to equitably educate the next generation of biomedical scientists and engineers.”

It continues: “We call on our colleagues to recognize the failings of our current hiring practices and adopt the guidelines provided here to diversify biomedical engineering departments so that we might collectively accelerate the impact, innovation, and power of our profession.”

The authors write that, as a result of inequitable hiring and the aforementioned lack of innovation and effectiveness of homogeneous teams, “As a profession, we are underperforming.”

The document is damning in terms of stating what a lack of diversity means not only for the development of diverse students who may not encounter role models who look like them, but also for the very health-centered outcomes that constitute the main thrust of the biological engineering profession. They write, “The lack of diversity in biomedical research hurts society as a whole: medical technologies such as the pulse oximeter are ineffective at best, or deadly at worst, for non-majority citizens with melanin-rich skin, which represent an increasingly large percentage of the U.S. demographic. The lack of foresight and oversight about the need for diverse teams in the development of such technologies perpetuates healthcare inequities on a global scale.”

Despite the fact that many or most bioengineering departments across the nation have written statements of intention expressing a desire to close the diversity gap, the authors write, “The faculty of our discipline remains overwhelmingly white, male, cishet, and able-bodied….we have been ineffective at improving diversity, and…our current strategies for recruitment and hiring will not get us there.”

Part of the challenge is underrepresentation among those earning PhDs, only 4.4 percent of whom come from historically excluded groups. But even if that number were to increase exponentially, the researchers say, a "conversion problem" would remain; that is, not enough people from these groups get into faculty positions, preventing increased diversity in academia.

While another often-considered strategy — increasing the number of faculty positions — would, on its own have little effect, a companion approach, that is, increasing the transition rate of PhD graduates from underrepresented groups to faculty from the current 0.25 percent to, say, 10 percent, “would change the fraction of assistant professors hired from historically excluded groups.” A model from the National Institutes of Health suggests that such an approach would increase transition to 12.4 percent by 2030 and 56.5 percent by 2080, assuming exponential growth in the diversity of the pipeline.

One driver of what the authors describe as “the disconnect between our intentions and outcomes to date” is, they say, that many in their profession “lack the education and skills needed to effectively hire faculty candidates from historically excluded groups. A kind of catch-22 situation also exists, seen in the fact that lack of diversity in a faculty proves to be a barrier to improving diversity. “Why would someone want to be ‘the first’ in an environment that has historically excluded individuals like them?” the authors posit, adding, “Prior to opening a search, we must improve the climate of our departments: specifically, the reward structures and the feeling of support people experience within an organization on a day-to-day basis. If a place does not feel “right,” individuals who are not part of the majority group will not come, will not be able to thrive, and will not stay.”

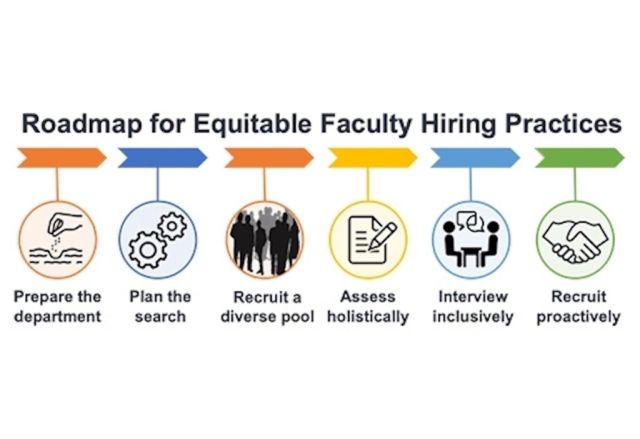

To address the various disconnects that have stood in the way of increasing diversity, the team came up with their “Roadmap for Equitable Hiring Practices.” Describing it as “especially salient for the cultural climate and needs of biomedical engineering departments,” they add, “Many of the strategies we present are universally applicable to all academic departments.”

The protocol includes six steps, which are to:

- Prepare the department

- Plan the search

- Recruit a diverse pool

- Assess holistically

- Interview inclusively

- Recruit proactively

Each of the steps is broken down into further steps that departments can take to achieve them. Together, they offer a clear way forward to address the many, often overlapping and interwoven constraints to achieving faculty diversity.

Author: James Badham

Original Source: https://engineering.ucsb.edu/news/road-map-increasing-faculty-diversity